Nicholas A. Abinya, University of Nairobi; Andrew Odhiambo, University of Nairobi; Esther Dindi, University of Nairobi; Peter Oyiro, University of Nairobi, and Sitna Mwanzi, Aga Khan University

Chronic myeloid leukaemia is a type of bone marrow cancer that goes on to affect the blood, then other organs and tissues. Previous research has linked it to exposure to high doses of radiation. The Conversation Africa’s Health Editor Joy Wanja Muraya asked a team of Kenyan experts to explain their research into what other factors might predispose people to this type of cancer.

What is chronic myeloid leukaemia and what encouraged your study?

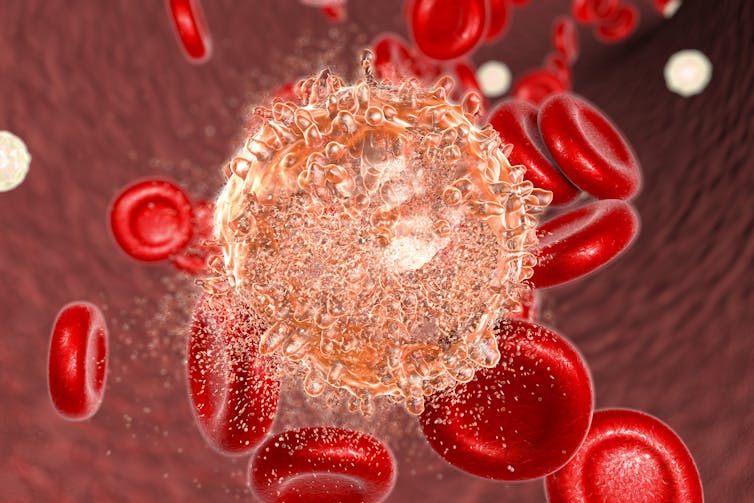

In sufferers of chronic myeloid leukaemia, the bone marrow produces too many white cells that gradually crowd the bone marrow, interfering with the normal production of blood cells.

One of the confirmed causes of this cancer is exposure to an atomic weapon or nuclear accident radiation. Other risks are not well established.

In a previous study, we found that there were no clear environmental factors associated with it. But we set off to investigate the association between patients’ occupations and whether personal and family history of cancer increased the chances of getting chronic myeloid leukaemia.

The study found that there was no clear link between occupation and contracting the cancer. There was familial correlation with common cancers in the population, suggesting epidemiologic - occurrence of disease within a population - rather than a genetic link.

These findings are important because they add to the general body of knowledge about chronic myeloid leukaemia and opens the door to new avenues of research to identify what risks might be behind it.

What was your study about?

We studied 398 patients aged between 18 and 80 years diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia. They were receiving treatment between November 2005 and April 2015 under a programme at Nairobi Hospital that offers free anti-cancer drugs. The clinic treats patients from Kenya and other East African countries including Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan, Burundi and Rwanda.

The study investigated the kinds of jobs these patients were involved in. We also interrogated whether a family history of other cancers had placed them at a higher risk of getting chronic myeloid leukaemia.

Of the 398 patients studied, only 297 had a family history of cancer recorded. Others didn’t know if there were such cases in their families.

Three patients had something peculiar: all worked at the same premises, one had chronic myeloid leukaemia and two acute myeloid leukaemia. The cases were:

a 33 year old information communication and technology male who was diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia. He worked for a mobile phone company in Nairobi.

A 40 year old female who was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia. She worked for the same telecommunications company and on the same floor. She was diagnosed in 2006.

A female worker in same company and office who was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia in 2011.

We concluded that these three employees in the same telecommunications office who developed myeloid leukaemias within a span of less than 10 years cannot be ignored. There is need for more intensive research in this area.

What makes this study unique and important in understanding blood cancers?

Generally, the best known cancer causing agents for all types of cancers include exposure to ionising radiation, chemicals and drugs, tobacco and alcohol consumption, infections, environmental pollutants and genetic factors.

For chronic myeloid leukaemia, the only confirmed link is with nuclear bomb radiation. Other associations such as exposure to benzene are largely weak. For example, other studies have failed to show a clear association between farming and the development of this cancer.

But a case control study in Iowa and Minnesota found pesticide exposure and other agricultural factors to be significant risk factors.

In our study, the numbers were too small to support a case that occupational exposure contributed to a person getting chronic myeloid leukaemia. Farming (the patients were mostly peasant farmers) topped the list of occupations at 19.7%, followed by those who worked in manual, outdoor jobs such as carpenters, builders, masons, painters and drivers, at 15.7%.

Evidence on linking cancer to electricity is mixed. On the one hand childhood leukaemia has been associated with exposure to residential electromagnetic fields. But other studies have failed to show any connection between high voltage power lines or mobile phones with leukaemia.

On a genetic link between chronic myeloid leukaemia, our study findings confirm earlier research that having a type of cancer in the family doesn’t increase a person’s chance to get this blood cancer. For example previous studies have shown that identical twins of patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia are not at greater risk than other siblings.

Cancers that were found among family members could be interpreted as having happened purely by chance since the cancers in question are the most common cancer types in our population.

Finally, there are two things we need to keep in mind from this study;

more research among workers in the telecommunications industry should be carried out.

whereas one can ignore the familial link between chronic myeloid leukaemia and other cancers seen in this study because of small numbers, we should track down defective common downstream pathways that cells use for survival signalling.

These could lead to cancer either by understanding the direct gene changes. It is also a chance to study epigenetics, the study of biological mechanisms that switch genes on and off.![]()

Nicholas A. Abinya, Professor of Medicine, section of Haematology and Oncology, University of Nairobi; Andrew Odhiambo, Assistant Lecturer in Internal Medicine & Medical Oncology/Haematology, University of Nairobi; Esther Dindi, Researcher, University of Nairobi; Peter Oyiro, Fellow Haematology-Oncology, University of Nairobi, and Sitna Mwanzi, Program Director, Department of Medicine, Aga Khan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.